Understanding pegging reveals how digital assets offer stability in volatile crypto markets. This financial engineering supports critical DeFi functions and global remittances.

While understanding Pegging in Crypto is important, applying that knowledge is where the real growth happens. Create Your Free Crypto Trading Account to practice with a free demo account and put your strategy to the test.

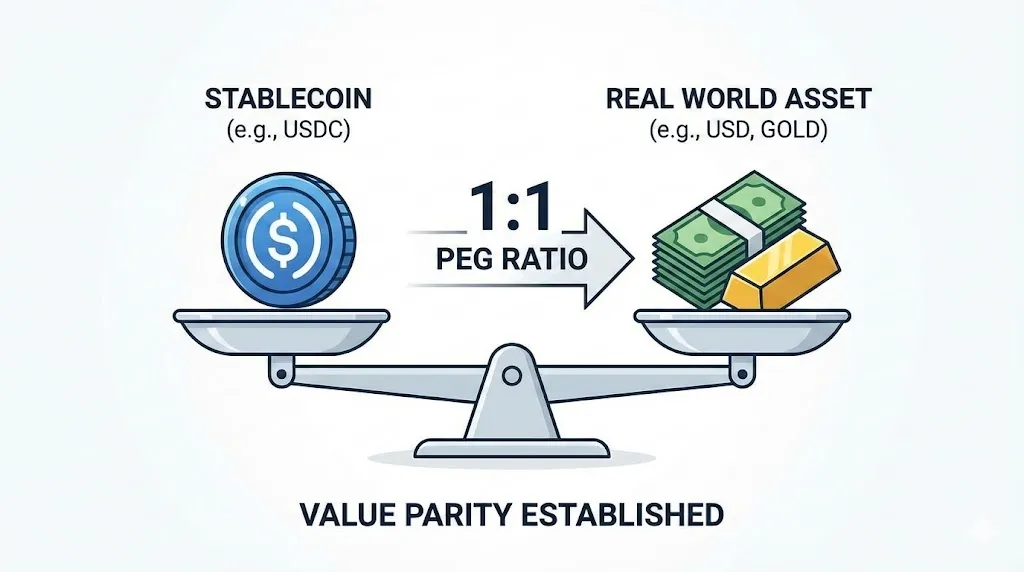

What Is a Peg in Cryptocurrency?

A peg in cryptocurrency establishes a fixed exchange rate for a digital asset against an external asset, typically a fiat currency like the US dollar. This mechanism ensures stablecoins hold a 1:1 value ratio with their underlying collateral or target price. This stability provides reliability in highly volatile cryptocurrency markets.

What is a 1:1 Value Ratio?

The core concept of a peg mandates that one unit of a stablecoin always equals one unit of its reference asset. For example, one USD Coin (USDC) consistently trades for one US dollar. This parity is crucial for users expecting predictable value in their digital transactions. The target ratio defines the precise value stablecoins aim to hold.

This consistent ratio simplifies transactions and reduces speculative risk compared to unpegged cryptocurrencies. Investors use stablecoins to enter and exit volatile positions without converting back to traditional fiat. This eliminates extra banking fees and delays for cryptocurrency users.

The Importance of Stability for Digital Assets

Stability significantly broadens the utility of digital assets beyond speculative trading. It provides a reliable medium of exchange for everyday purchases, international remittances, and predictable lending within decentralized finance (DeFi). Volatility often hinders cryptocurrency adoption for mainstream use cases.

Stablecoins reduce the risk of value fluctuations during transactions, making them practical for payments. They also offer a safe haven during market downturns, preserving capital when other crypto assets decrease. This dependable value proposition underpins the functionality of many blockchain applications.

How Stablecoins Maintain Their Peg?

Stablecoins maintain their peg through a combination of asset collateralization, algorithmic adjustments, and market arbitrage incentives. These interconnected mechanisms work to absorb market fluctuations and restore the 1:1 target ratio when deviations occur. Different models prioritize different strategies.

Asset Backing and Reserve Management

Asset backing involves holding reserves of traditional assets, like fiat currency or other cryptocurrencies, to cover the value of issued stablecoins. Fiat-collateralized stablecoins, such as Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC), maintain a 100% or 1:1 cash equivalent reserve. This means for every stablecoin issued, an equal value of reserve assets exists.

These reserves are typically held by custodians in bank accounts or short-term, highly liquid investments. Regular audits verify the existence and sufficiency of these reserves, providing transparency and trust. This direct collateralization offers a straightforward method for value stability.

Algorithmic Supply Adjustments (Mint and Burn)

Algorithmic stablecoins maintain their peg without direct asset collateralization. Instead, they rely on smart contracts to dynamically adjust their supply based on market price. When the stablecoin’s price deviates from its peg, the system executes automated minting or burning operations.

If the stablecoin trades below its target price, the protocol reduces supply by burning tokens. This creates scarcity and drives the price back up. Conversely, if the price exceeds the peg, new tokens are minted and sold, increasing supply and lowering the price. These smart contract-driven adjustments aim to restore the 1:1 ratio through economic incentives.

Market Arbitrage and Incentivized Trading

Market arbitrage plays a critical role in peg maintenance by creating profit opportunities for traders when a stablecoin deviates from its peg. Arbitrageurs exploit these small price discrepancies to profit and, in doing so, push the stablecoin’s price back to its intended value. This mechanism does not rely on the issuer directly.

If a stablecoin dips to $0.99, arbitrageurs buy large quantities to redeem them with the issuer for $1.00 (or swap for $1.00 of another asset), profiting from the $0.01 difference per coin. This buying pressure increases the price back towards $1.00. Conversely, if the stablecoin trades at $1.01, traders sell it for $1.00 worth of collateral, reducing its price.

This continuous buying and selling pressure from arbitrageurs helps maintain the stablecoin within a narrow trading bandwidth, such as between $0.99 and $1.01. It is a powerful, decentralized force for stability.

Ready to Elevate Your Trading?

You have the information. Now, get the platform. Join thousands of successful traders who use Volity for its powerful tools, fast execution, and dedicated support.

Create Your Account in Under 3 MinutesTypes of Pegging Models Explained

Four primary pegging models exist in the cryptocurrency space, each employing distinct strategies to maintain value parity. These models include fiat-collateralized, crypto-collateralized, commodity-backed, and algorithmic designs. Understanding their differences clarifies how stablecoins operate.

Fiat-Collateralized Pegs (USDT, USDC)

Fiat-collateralized stablecoins are backed by reserves of traditional currencies, primarily the US dollar. These stablecoins like Tether (USDT), USD Coin (USDC), and Binance USD (BUSD) are among the most common types. Their value is directly tied to an equal amount of fiat currency held in a bank account.

Issuers typically maintain a 100% reserve requirement against the stablecoins in circulation. This direct backing aims to provide a clear and verifiable mechanism for stability. External audits periodically confirm these reserves, though transparency varies among issuers.

Crypto-Collateralized Pegs (Over-Collateralization)

Crypto-collateralized stablecoins use other cryptocurrencies as collateral, rather than fiat currency. Since cryptocurrencies are inherently volatile, these models employ over-collateralization to absorb price swings. This means more than $1 worth of crypto collateral backs each $1 of stablecoin.

For instance, a stablecoin might require $1.50 worth of Ether (ETH) to mint $1 of the stablecoin. If the ETH collateral value decreases, a liquidation mechanism might sell off a portion of the collateral to protect the peg. MakerDAO’s DAI is a prominent example of a crypto-collateralized stablecoin.

Commodity-Backed Pegs (Gold, Oil)

Commodity-backed stablecoins link their value to tangible assets like gold, oil, or even real estate. Each stablecoin token represents a fractional ownership of the underlying commodity. This offers an alternative to fiat or crypto backing.

Examples include Pax Gold (PAXG), which is backed by physical gold held in vaults. This model allows investors to gain exposure to commodities in a digitized, easily transferable form without direct physical ownership. Regulatory frameworks often vary for these assets compared to fiat-backed alternatives.

Algorithmic (Non-Collateralized) Models

Algorithmic stablecoins utilize sophisticated smart contracts and economic incentives to maintain their peg without direct collateral. They expand or contract the supply of tokens based on market demand. This involves a mint-and-burn mechanism to stabilize the price.

If the stablecoin’s price falls below $1, the protocol incentivizes users to burn tokens, reducing supply. If the price rises above $1, it incentivizes users to mint new tokens, increasing supply. TerraUSD (UST), prior to its collapse, was a prominent algorithmic stablecoin. This model presents significant challenges regarding stability during extreme market conditions.

Risks and Challenges of Peg Maintenance

Maintaining a stable 1:1 peg presents significant risks and challenges, particularly during periods of high market volatility or economic stress. These include potential depegging events, security vulnerabilities, and the complexities of target-zone models. Understanding these risks is crucial for participants.

Depegging Events and Price Volatility

A depegging event occurs when a stablecoin significantly deviates from its intended 1:1 value ratio. This happens when market confidence erodes, collateral is insufficient, or arbitrage mechanisms fail. A stablecoin is technically considered “depegged” if its value consistently falls below $0.98 or rises above $1.02 for an extended period.

Such events erode investor trust and can trigger broader market instability, as seen with the collapse of TerraUSD. Factors like reserve mismanagement, regulatory uncertainty, or systemic market shocks increase the likelihood of depegging. Restoration of the peg requires substantial intervention or market correction.

Security Threats and Smart Contract Risks

Stablecoins, especially those reliant on smart contracts, face various security threats. Smart contract vulnerabilities can lead to exploits, allowing malicious actors to drain collateral or manipulate supply. Centralized reserve management also introduces custodial risk.

The security of the underlying blockchain network and the robustness of auditing practices are critical. Any breach or exploit compromises the integrity of the stablecoin’s backing. This directly impacts its ability to maintain its peg. Vigilant monitoring and frequent security audits reduce these risks.

Target-Zone Models and Trading Bandwidths

Target-zone models refer to the mathematical boundaries within which a stablecoin is considered “stable.” These models define an acceptable price range, such as $0.99 – $1.01, where minor fluctuations are tolerated. The peg aims to keep the asset within this narrow bandwidth.

The efficiency of these models dictates the stablecoin’s resilience during market stress.

Turn Knowledge into Profit

You've done the reading, now it's time to act. The best way to learn is by doing. Open a free, no-risk demo account and practice your strategy with virtual funds today.

Open a Free Demo AccountThe Future of Pegged Assets in the U.S. Economy

The future of pegged assets within the U.S. economy hinges significantly on evolving regulatory frameworks and technological advancements. As stablecoins gain broader adoption for payments and investments, policymakers are scrutinizing their stability, transparency, and systemic risks. This scrutiny aims to integrate digital assets safely.

Regulatory bodies in the U.S. propose comprehensive guidelines to ensure stablecoin issuers maintain 1:1 reserves and undergo regular audits. This would mandate clearer reporting and accountability, enhancing consumer protection. The potential for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) also influences the landscape.

Such regulations seek to mitigate risks associated with depegging and ensure financial stability across traditional and digital markets. Innovation continues with new hybrid models combining collateralization with algorithmic features, aiming for greater resilience. These developments shape stablecoins into a more robust component of the global financial system.

Key Takeaways

- Stability is Purpose: Pegging establishes a crucial 1:1 value ratio, making stablecoins a reliable medium of exchange in volatile markets.

- Model Diversity: Parity is maintained via three primary models: fiat-collateralized (cash reserves), crypto-collateralized (over-collateralization), and algorithmic (mint and burn).

- Arbitrage as a Safeguard: Decentralized market arbitrage provides the continuous buying and selling pressure needed to keep stablecoins within narrow trading bandwidths.

- Risk Awareness: Depegging events and smart contract vulnerabilities remain significant challenges that require constant monitoring and robust reserve management.

Bottom Line

Stablecoins serve as the bedrock of the modern digital economy, bridging the gap between traditional finance and blockchain innovation. While mechanisms like over-collateralization and algorithmic adjustments offer sophisticated pathways to stability, the ultimate success of a peg rests on transparency and market trust. As the landscape evolves under new regulatory eyes in 2025, understanding these mechanics is no longer optional—it is essential for navigating the future of decentralized finance.